Looking for a Bottom in Mortgage REITs

(Drawing credit)

Mortgage REITs try to do more with less, leveraging shareholders' equity by borrowing multiples of core capital and investing all of the proceeds in mortgages, bonds and other debt secured by real estate. This leverage works wonders in years when yield curve spreads are favorable, and miserably when they are not. . . .

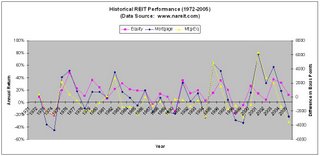

Among the various REIT sectors tracked by the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (NAREIT), mortgage REITs were the worst performer during 2005, suffering a loss of 23%, compared to an average gain of 12% for all equity REITs (see performance statistics). So far this year, mortgage REITs continue to lag, trading flat through the end of February, versus a 9% gain for equity REITs. What's behind this underperformance of mortgage REITs and when might we expect a rebound?

Equity REITs have benefited from the lengthy bull market in real estate, and their stock prices recently have been lifted even higher by the keen interest private investment funds are showing in acquiring undervalued REIT shares and taking the publicly traded companies private (e.g., Blackstone Group buying office REIT CarrAmerica (CRE) for $5.6 billion). Mortgage REITs, on the other hand, are a different beast altogether. With their portfolios of mortgages instead of real property, mortgage REITs trade somewhat like leveraged bonds, showing more sensitivity to interest rates and the yield curve than to rents, occupancy and property operating income. Among the largest of the mortgage REITs by market capitalization are Thornburg Mortgage (TMA), New Century Financial (NEW), newly formed KKR Financial (KFN), American Home Mortgage (AHM), and Annaly Mortgage Management (NLY).

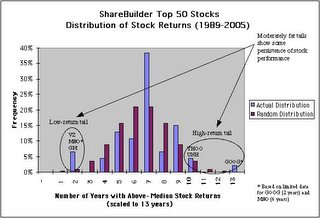

The graph to the right shows the annual performance of equity and mortgage REITs for the 34-year period from 1972 through 2005. Notice that returns of mortage REITs are considerably more cyclical than returns of equity REITs. Following four years of underperformance from 1997 to 2000, mortgage REITs showed spectacular gains for the three years from 2001 to 2003, producing returns averaging in excess of 50% per annum. Then, in 2004, mortgage REITs began to slip back into a funk, and by 2005 were lagging their equity REIT brethren by a wide margin.

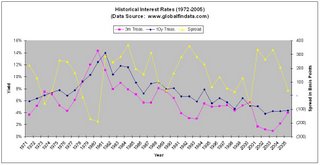

The graph to the right shows the annual performance of equity and mortgage REITs for the 34-year period from 1972 through 2005. Notice that returns of mortage REITs are considerably more cyclical than returns of equity REITs. Following four years of underperformance from 1997 to 2000, mortgage REITs showed spectacular gains for the three years from 2001 to 2003, producing returns averaging in excess of 50% per annum. Then, in 2004, mortgage REITs began to slip back into a funk, and by 2005 were lagging their equity REIT brethren by a wide margin. The cyclicality of mortgage REITs is due to the dependence of their underlying business on the yield curve. Managers of mortgage REITs typically leverage shareholder equity by borrowing additional funds short-term and investing into longer term debt instruments secured by real properties, similar to how banks and S&Ls run their deposit and lending businesses. Interest rate swaps and other financial derivatives may be used to manage yield curve risk, but mortgage REITs nevertheless show more sensitivity to interest rates than do equity REITs. In the graph to the right, observe how the yield spread between the 10-year Treasury bond and the 3-month T-bill shows a cyclicality analogous to what we saw above for mortgage REITs.

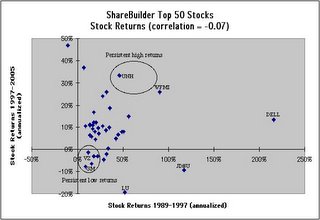

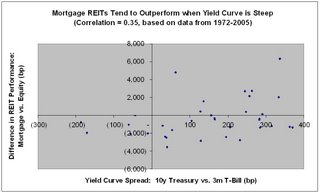

The cyclicality of mortgage REITs is due to the dependence of their underlying business on the yield curve. Managers of mortgage REITs typically leverage shareholder equity by borrowing additional funds short-term and investing into longer term debt instruments secured by real properties, similar to how banks and S&Ls run their deposit and lending businesses. Interest rate swaps and other financial derivatives may be used to manage yield curve risk, but mortgage REITs nevertheless show more sensitivity to interest rates than do equity REITs. In the graph to the right, observe how the yield spread between the 10-year Treasury bond and the 3-month T-bill shows a cyclicality analogous to what we saw above for mortgage REITs. By examining a scatter plot of yield curve spread (10-year Treasury yield minus 3-month T-bill yield) versus the difference in performance between equity and mortgage REITS (mortgage REIT return minus equity REIT return) for the years from 1972 to 2005, we can extract the relationship between the yield curve and mortgage REIT performance. When the yield curve is steep (long-term interest rates significantly higher than short-term interest rates), mortgage REITs have historically shown higher total returns. On the other hand, when the yield curve becomes flat or inverted (long-term interest rates comparable to or lower than short-term interest rates), mortgage REITs have typically underperformed equity REITs, as has been the case for the past two years. The basic mechanism behind this cyclical overperformance-underperformance behavior is that, particularly through using leverage, mortage REITs benefit from their ability to borrow at low interest rates and invest at higher long-term rates when the yield curve is steep, but have a much harder time finding sufficient yield pick-up from credit spreads alone in a flattish yield curve environment like the one we are now in (3-month T-bill at 4.5% vs. 10-year Treasury at 4.8%).

By examining a scatter plot of yield curve spread (10-year Treasury yield minus 3-month T-bill yield) versus the difference in performance between equity and mortgage REITS (mortgage REIT return minus equity REIT return) for the years from 1972 to 2005, we can extract the relationship between the yield curve and mortgage REIT performance. When the yield curve is steep (long-term interest rates significantly higher than short-term interest rates), mortgage REITs have historically shown higher total returns. On the other hand, when the yield curve becomes flat or inverted (long-term interest rates comparable to or lower than short-term interest rates), mortgage REITs have typically underperformed equity REITs, as has been the case for the past two years. The basic mechanism behind this cyclical overperformance-underperformance behavior is that, particularly through using leverage, mortage REITs benefit from their ability to borrow at low interest rates and invest at higher long-term rates when the yield curve is steep, but have a much harder time finding sufficient yield pick-up from credit spreads alone in a flattish yield curve environment like the one we are now in (3-month T-bill at 4.5% vs. 10-year Treasury at 4.8%).Whether mortgage REITs will recover from their current slump anytime soon depends on what happens to interest rates. The recent peak (6.5% in May 2000) and trough (1.0% in June 2003) of the targeted fed funds rate correspond approximately to the transition points demarcating periods of underperformance (1997-2000), outperformance (2001-2003) and a reversion to underperformance (2004 to present) by mortgage REITs over the past decade. If yesterday's FOMC decision under new fed chairman, Ben Bernanke, to raise the fed funds rate to 4.75% is the last in the current series of rate hikes initiated under Greenspan, and if the yield curve begins to steepen again, we should expect to see a turnaround in mortgage REITs over the upcoming year. However, given that the FOMC indicated in their press release that "some further policy firming may be needed," it seems more likely that short-term rates will continue to rise another 25 bp or so, prolonging the flat yield curve environment and continuing to put pressure on the profit margins of mortgage REITs. However, cycles being what they are, the day will certainly come when mortgage REITs once again rise from the dead, presenting an opportunity for investors who are able to time the market correctly.

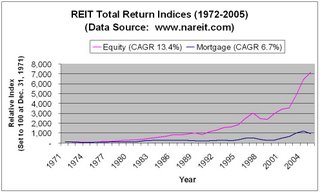

I close with a caveat based on the historical performance of mortgage and equity REITs. As NAREIT data from 1972 to 2005 indicate, equity REITs have returned 13.4% per annum, versus just 6.7% per annum for mortgage REITs over the past 34 years. The graph to the right shows how a $100 buy-and-hold position in the mortgage REIT index on December 31, 1971, would be worth about $1,000 today, while the same-size investment in the equity REIT index would have grown a whopping seven-fold more to $7,000!

I close with a caveat based on the historical performance of mortgage and equity REITs. As NAREIT data from 1972 to 2005 indicate, equity REITs have returned 13.4% per annum, versus just 6.7% per annum for mortgage REITs over the past 34 years. The graph to the right shows how a $100 buy-and-hold position in the mortgage REIT index on December 31, 1971, would be worth about $1,000 today, while the same-size investment in the equity REIT index would have grown a whopping seven-fold more to $7,000!Upshot: Mortgage REIT investing can be very rewarding if timed right; however, the more reliable long-term play may be to allocate a greater amount of investment capital to equity REITs and simply hang on for the ride.