Win-Loss Percentages, or How Having a Slight Edge Goes a Long Way

You might have heard that good traders are right only a little more than half of the time. In other words, having just a few more "up days" than "down days" can and does make all the difference when it comes to overall portfolio performance.

For an example of how daily wins and losses translate into longer-term returns, we can look at the price movement of the 30 components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average during 2005. The top performer for the year was Boeing (BA), up 41%, on a pick-up in large airplane orders as the company recoups market share taken in recent years by European competitor Airbus. The worst performer was GM (GM), down 50% for the year, on erosion of market share as American auto makers lose ground to Toyota, Honda and others. Among the 252 trading days during 2005, Boeing rose 130 days (52% of the time) and fell 122 trading days. During the same period of time, GM was up 106 days (42% of the 252 trading days) and down the remaining 146 trading days. Here we can see how winning (i.e., having an up-day) 52% of the time produces such a dramatically different result than winning a lesser 42% of the time. Just as in professional baseball, a few point spread in win-loss percentages is all it often takes to distinguish between a first place and a last place finisher.

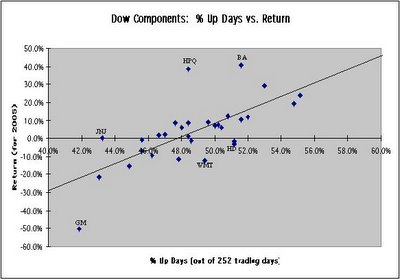

The diagram below displays the performance of each of the 30 components of the Dow during 2005, showing how the percentage of days that a stock rises relates to its overall percentage return for the period. The data indicate a strong correlation (0.70) between winning days and overall return. The best-fit regression line has a slope of 3.8, i.e., a 1% increase in winning days (2 to 3 additional up-days during the 252-day trading year) typically leads to a 3.8% increase in return for the year.

From a trading perspective, we can express this result as follows: If a trader is able to convert just one additional trading day during the year from a loss to a win, he typically boosts his annual performance by about 1.5%. Ten additional winning days (i.e., two weeks) can be expected to elevate annual performance by a full 15%. In actual market performance, the impact can even be greater--as mentioned above, a difference in outcome on just 24 trading days (130 up-days for Boeing vs. 106 up-days for GM) is all it took to create the gaping 91 percentage point chasm between the best (Boeing up 41%) and worst (GM down 50%) performers in the Dow during 2005. Clearly, having a slight edge goes a very long way in investing.

The above scatter plot also provides a "reversion to the mean" trade idea for anyone interested: I have labeled the points corresponding to the stocks showing the largest deviations from the regression line. Among these outliers, Hewlett Packard (HPQ), Boeing (BA) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) exhibit the greatest outperformance in return versus what would be expected based on the percentage of up-days. The greatest underperformers with respect to the regression line are GM (GM), Wal-Mart (WMT) and Home Depot (HD). Based on reversion-to-the-mean thinking--which has a plausible footing in investor over-reaction theory (i.e., investors tend to overbuy when stocks rise and oversell when stocks fall)--one might predict that the 2005 outperformers are good short candidates in 2006, while the 2005 underperformers should be considered for long positions. (Caveat: I have run some reversion-to-the-mean simulations on shorter-term trading horizons but have not managed to uncover consistently reliable excess profits. So, proceed at your own risk. More optimistically, keep in mind that only a slight edge is all that is needed to outperform the market.)

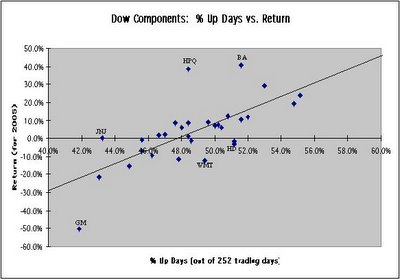

For an example of how daily wins and losses translate into longer-term returns, we can look at the price movement of the 30 components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average during 2005. The top performer for the year was Boeing (BA), up 41%, on a pick-up in large airplane orders as the company recoups market share taken in recent years by European competitor Airbus. The worst performer was GM (GM), down 50% for the year, on erosion of market share as American auto makers lose ground to Toyota, Honda and others. Among the 252 trading days during 2005, Boeing rose 130 days (52% of the time) and fell 122 trading days. During the same period of time, GM was up 106 days (42% of the 252 trading days) and down the remaining 146 trading days. Here we can see how winning (i.e., having an up-day) 52% of the time produces such a dramatically different result than winning a lesser 42% of the time. Just as in professional baseball, a few point spread in win-loss percentages is all it often takes to distinguish between a first place and a last place finisher.

The diagram below displays the performance of each of the 30 components of the Dow during 2005, showing how the percentage of days that a stock rises relates to its overall percentage return for the period. The data indicate a strong correlation (0.70) between winning days and overall return. The best-fit regression line has a slope of 3.8, i.e., a 1% increase in winning days (2 to 3 additional up-days during the 252-day trading year) typically leads to a 3.8% increase in return for the year.

From a trading perspective, we can express this result as follows: If a trader is able to convert just one additional trading day during the year from a loss to a win, he typically boosts his annual performance by about 1.5%. Ten additional winning days (i.e., two weeks) can be expected to elevate annual performance by a full 15%. In actual market performance, the impact can even be greater--as mentioned above, a difference in outcome on just 24 trading days (130 up-days for Boeing vs. 106 up-days for GM) is all it took to create the gaping 91 percentage point chasm between the best (Boeing up 41%) and worst (GM down 50%) performers in the Dow during 2005. Clearly, having a slight edge goes a very long way in investing.

The above scatter plot also provides a "reversion to the mean" trade idea for anyone interested: I have labeled the points corresponding to the stocks showing the largest deviations from the regression line. Among these outliers, Hewlett Packard (HPQ), Boeing (BA) and Johnson & Johnson (JNJ) exhibit the greatest outperformance in return versus what would be expected based on the percentage of up-days. The greatest underperformers with respect to the regression line are GM (GM), Wal-Mart (WMT) and Home Depot (HD). Based on reversion-to-the-mean thinking--which has a plausible footing in investor over-reaction theory (i.e., investors tend to overbuy when stocks rise and oversell when stocks fall)--one might predict that the 2005 outperformers are good short candidates in 2006, while the 2005 underperformers should be considered for long positions. (Caveat: I have run some reversion-to-the-mean simulations on shorter-term trading horizons but have not managed to uncover consistently reliable excess profits. So, proceed at your own risk. More optimistically, keep in mind that only a slight edge is all that is needed to outperform the market.)

4 Comments:

Excellent blogging. You can find some information about the stock market in books and magazines, but it's a lot easier on the web, especially blogs like yours.

I would like to talk about trading as opose to buy and hold. Although I am not a buy and hold forever investor' I do believe in holding my stocks for a considerable period of time years in some cases. I don't think traders ever consider the time spent on all their trades which must be very great.

You should be able to get more than just a slight edge.

You made my day! I am very happy and relaxed too that I find this blog. I was looking for the matter discussed in blog post. If you have some more blogs on the material please share those as well. Thanks a lot and keep sharing such useful information.

Intraday Tips

Post a Comment

<< Home